Writing for ISD’s blog, The Diplomatic Pouch, ISD’s director of programs and research, Kelly McFarland, puts recent U.S.-China tensions in historical perspective:

Threats against a social media app, sanctions against politicians and businesses, and the closure of a consulate: In the past few weeks, the Trump administration has ratcheted up its rhetoric and actions toward China.

President Trump has threatened to ban the popular Chinese-owned social media app Tik Tok, his administration sanctioned the Chinese-backed chief executive of Hong Kong, Carrie Lam, and will pursue further sanctions against a Chinese company for its role in the treatment of ethnic Uighurs. These actions come just after the administration closed the Chinese consulate in Houston — the Chinese closed the U.S. consulate in Chengdu in response.

Most recently, Health Secretary Alex Azar became the “highest-ranking U.S. official to visit Taiwan in four decades, in a pointed signal of support for the self-governing Island that has infuriated Beijing.” China responded last week by flying military jets over the de facto border into Taiwanese airspace.

As Axios’ China specialist Bethany Allen-Ebrahimian noted, “it seems as if we’ve seen a decades’ worth of hawkish policies proposed or executed just in the past few weeks.”

Pushing a seven-decades old button

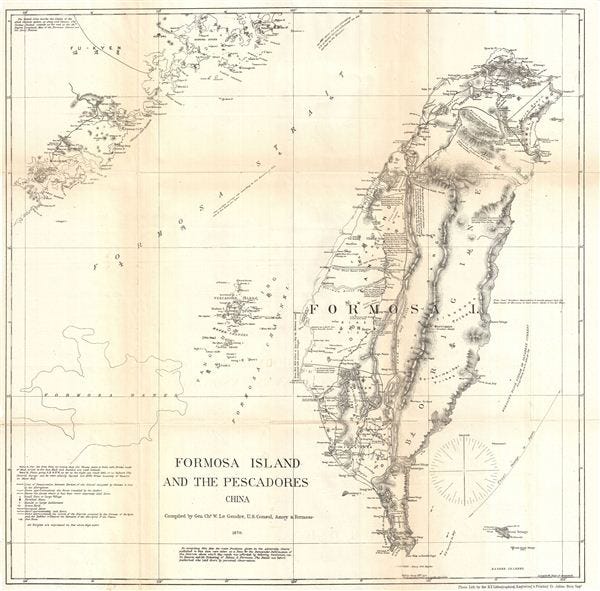

All of the Trump administration’s threats and actions amount to an escalation in the growing rift between the two countries. None has as charged a history behind it as U.S.-China relations over Taiwan. Formerly known as Formosa, this island nation has ebbed and flowed as a source of conflict between the two great powers.

Taiwan was never more of a hotspot than in the 1950s. September 3rd, in fact, will mark the anniversary of China’s 1954 shelling of an island that set off what would be the first of two Taiwan Strait crises in that decade.

After defeat in the civil war in 1949 at the hands of Mao Zedong’s communists, the nationalists under Chiang Kai-shek fled to Formosa. Over the years, Chiang harbored dreams of invading the mainland to reclaim leadership of a united China. Meanwhile, across the strait, Mao planned to take Formosa to reunify China under communist control and end the nationalist threat. The outbreak of the Korean War in 1950, and communist China’s intervention on the North Korean side, delayed any future invasion of Formosa from Beijing, while the nationalists were in no position to launch their own offensive of the mainland.

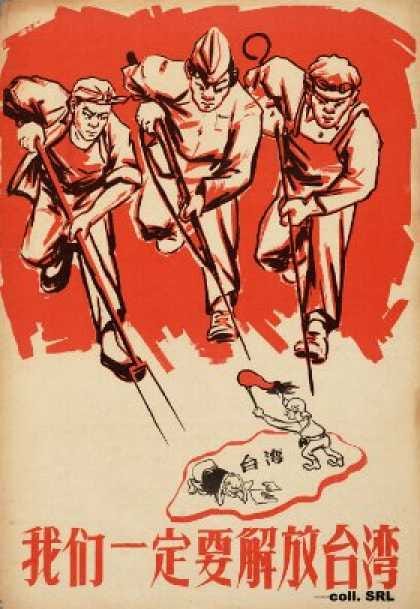

After the Korean War armistice in 1953, the Indochina War between Vietnamese communist forces (with communist Chinese aid) and the French ended in the spring of 1954. Beijing now turned its attention to Taiwan. Mao began a “Liberate Taiwan” propaganda campaign in mid-1954. Against this backdrop, the communist forces began shelling the nationalist-controlled island of Quemoy on September 3, 1954, setting off one of the most dangerous episodes of the Eisenhower presidency and the nuclear age as a whole.

According to Gordon H. Chang and He Di, orders to shell Quemoy were not the opening salvo to an invasion of the island, but “a specific and limited response to what was perceived as an increase in U.S. and nationalist provocations in the area” and rumors of a mutual defense pact between Washington and Taipei.

Chinese communist leaders also viewed the shelling campaign as a domestic propaganda victory. What made the shelling climb the ladder of importance in Washington, though, was, in part, the death of two American military advisors and the apparent failure of U.S. deterrence (the Chinese viewed this deterrence as “military provocations”).

New look, new problem

The Eisenhower administration came into office in early 1953 full of ardent Republican Cold Warriors, with a pronounced, hardline rhetoric of “rolling back” communist expansion. However, Ike was also a fiscal conservative, and was appalled at recent levels of U.S. defense expenditure, which he viewed as unsustainable. The question became how Washington could win the Cold War while also reining in the budget. After a detailed policy review, the administration settled on the “New Look” strategy. As George Herring describes it:

To permit substantial budget cuts without weakening the nation’s defense posture, the New Look relied on nuclear weapons — “more bang for the buck,” it was called. Dulles publicly outlined a concept of “massive retaliation” by which the United States would respond to aggression at times and places and with weapons of its own choosing, leaving open the use of nuclear weapons against the Soviet Union itself.

The administration was not sure if the shelling meant a prelude to invasion, or a test of American resolve. Either way, it was serious, and the recent French withdrawal from Indochina — after Eisenhower refused to enter the fray militarily — only added to the dilemma. Abandonment of the nationalists would “undermine Chiang, damage America’s prestige in Asia, and cause a firestorm of protest by the Asia First Republicans at home.” Full-throated support of the nationalists’ control of the islands risked war with China. Eisenhower and Dulles tried to stall. The administration signed a defense security treaty with the nationalists, which only included the defense of Taiwan and the Pescadores islands, and did not specifically name Quemoy and Matsu.

After the Quemoy shelling in 1954, the situation escalated drastically in January 1955 when communist Chinese forces bombed and then invaded a portion of the nationalist-held Tachen island group. Because the new U.S.-nationalist treaty omitted specific mention of the offshore islands, Mao and his “commanders concluded that the United States would not join in active defense.” Eisenhower and Dulles persuaded the nationalists to give up their hold on the Tachens, and the United States provided aid to evacuate nationalist forces. But the administration also “clarified the ambiguous language of the mutual defense treaty.” The United States would now defend Quemoy and Matsu if the communists attacked. By the end of the month, the United States Congress also passed the “Formosa Resolution” to give Ike the authority to defend Taiwan militarily and to respond to incursions into Quemoy and Matsu too if they believed an attack on Taiwan might follow.

Posturing and rhetoric escalated throughout the rest of the winter and into spring. In early March, secretary of state Dulles announced in a nationally televised speech that the United States would use atomic weapons to defend its interests in Asia. Eisenhower concurred. Wasn’t that what the New Look was all about after all?

Historians are torn on the success of the administration’s sabre rattling. Regardless, Chinese foreign minister Zhou Enlai told the Bandung Conference of non-aligned nations in late April that the Chinese wanted no war with the United States. The communists significantly curtailed shelling of the island. Even if the United States’ nuclear brinkmanship won the moment, it also sped up China’s efforts to seek a nuclear weapon. They successfully detonated one in 1964. Would Eisenhower have dropped nuclear bombs on China over self-described insignificant islands? Thankfully, the world never had to find out.

Outside of Cold War historians, this episode is largely forgotten, but it highlights what a long-standing issue Taiwan has been for the United States and China. The U.S. and China have had serious moments of tension in the past, from Korea, to Taiwan. to Vietnam, and issues such as the 1954 Taiwan Strait Crisis demonstrate that leaders need to be careful lest misperception and miscalculation lead to war.

In light of increasing U.S.-China tensions today, both sides need to keep this history in mind. We could see rhetoric and action on the American side increase even more as we approach the November presidential election. One of the Trump campaign’s major attacks on Democratic nominee Joe Biden is that he is soft on China, which could easily lead to Trump exacerbating a foreign policy issue for domestic political gain. In the long run, though, Trump’s current hardline could provide a potential Biden administration an opportunity in early 2021 to calm the situation, establish a more coherent China policy, and to engage in substantive discussions with Beijing.